Coming out of Egypt, coming out of Exile, coming out of a period of despair proves harder than expected. When the ancient Israelites left the bondage of Egypt, one would have thought they would have been glad to leave it behind and to enjoy their newfound freedom. But as Moses soon found out, it wasn’t that easy. When the going gets tough, the people don’t go shopping, they go complaining. Why did you takes us out of Egypt and back us up to the sea, ready pickings for Pharaoh’s army? Were there not graves enough in Egypt? Why did you bring us out in this wilderness? There’s not enough water. There’s not enough to eat.

It’s easy enough to see the ancient Israelites as whiners, but on the other hand, they had a point. In Egypt the work may have been hard, the conditions may have been dreadful, but they weren’t roaming around lost, in a vast unknown every day.

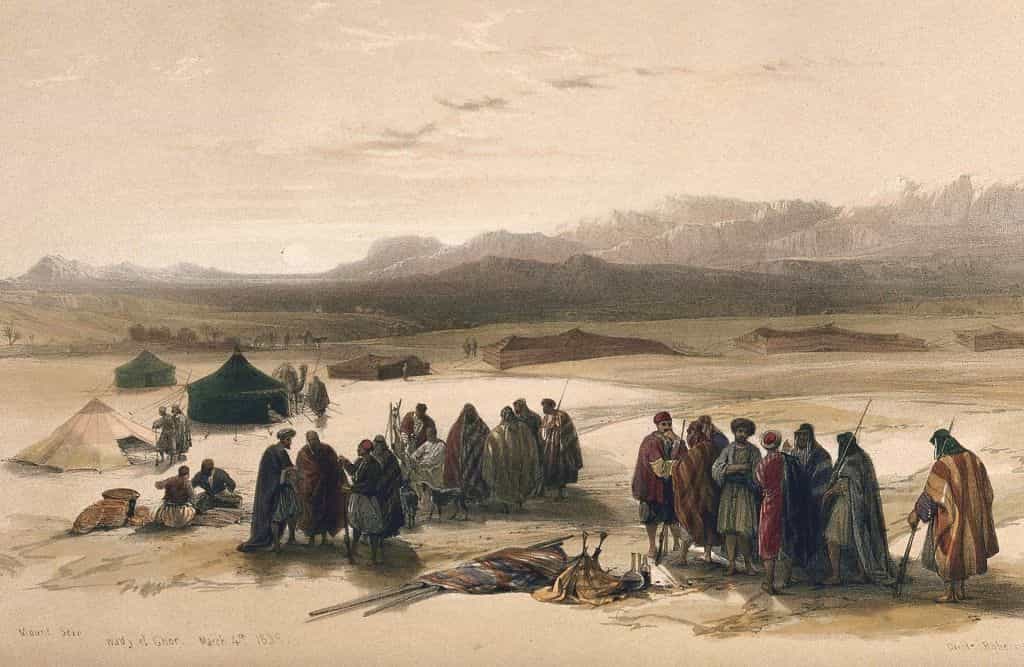

Encampment in the desert, with Mount Seir in the distance. Colored lithograph by Louis Haghe after David Roberts, 1849.

Leaving Babylon Was Just as Hard

More than a millennium later, the Israelites coming home from exile in Babylon encountered a related, though different, reality. While in Babylon they sang longing laments for their homeland, for Zion. Their poetry gave eloquent testimony to their sorrow:

Psalms 137:1-4 (NRSV): By the rivers of Babylon – there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion. On the willows there we hung up our harps. For there our captors asked us for songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!” How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?

In 587 b.c.e. Nebuchudnezzar smashed what remained of Israel’s promised land, left the holy temple of Solomon but a pile of rubble and carried the people off to Babylon. There they wept their tears, yearning for a return of former times.

Forty-eight years later there came another change in power. The Persians overcame the Babylonians, and the exiles found themselves at the hands of a more benevolent governance. Persia, unlike Babylon, granted great autonomy to its subjects. Cyrus the great let the exiles go home, let them repatriate Judea, and instructed them to rebuild their temple. There hardly could have been more of an answer to their prayers.

But, again, things as reality seldom work out the way they are dreamed. Despite Cyrus’s generous edict, once the people got re-settled, their commitment seems to have flagged. For the whole time in exile, they had looked to rebuild their home and center of worship. But once there, it seems that a modest prosperity was established, that life took on something of a ho-hum quality, and the temple lay unfinished.

The Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem as depicted by artist James Tissot.

the temple lies in ruin

It lay unfinished twenty years later, when Haggai wrote this morning’s passage. Haggai looks at the result of the apathy. He looks at the stones partially restored, but now the work site is quiet. Grass and weeds have overgrown parts of the construction. It has the look of abandonment, even in its current usage. It must have been something like those movies we see today that take place after the world has faced collapse. You see the remnant of what were once grand structures, but now they are burned out relics. You see people gathering around flaming oil barrels to warm themselves. What once was is evident in the ruin, but now it is being used as a shadow of its former self. I imagine the temple in Jerusalem must have been something like that, and Haggai turns to the people looking to ignite their passion for the restoration of former things.

3 Who is left among you that saw this house in its former glory? How does it look to you now? Is it not in your sight as nothing? 4 Yet now take courage, O Zerubbabel, says the Lord; take courage, O Joshua, son of Jehozadak, the high priest; take courage, all you people of the land, says the Lord; work, for I am with you, says the Lord of hosts, 5 according to the promise that I made you when you came out of Egypt.

Archaeologist studying the ruins of ancient Israel

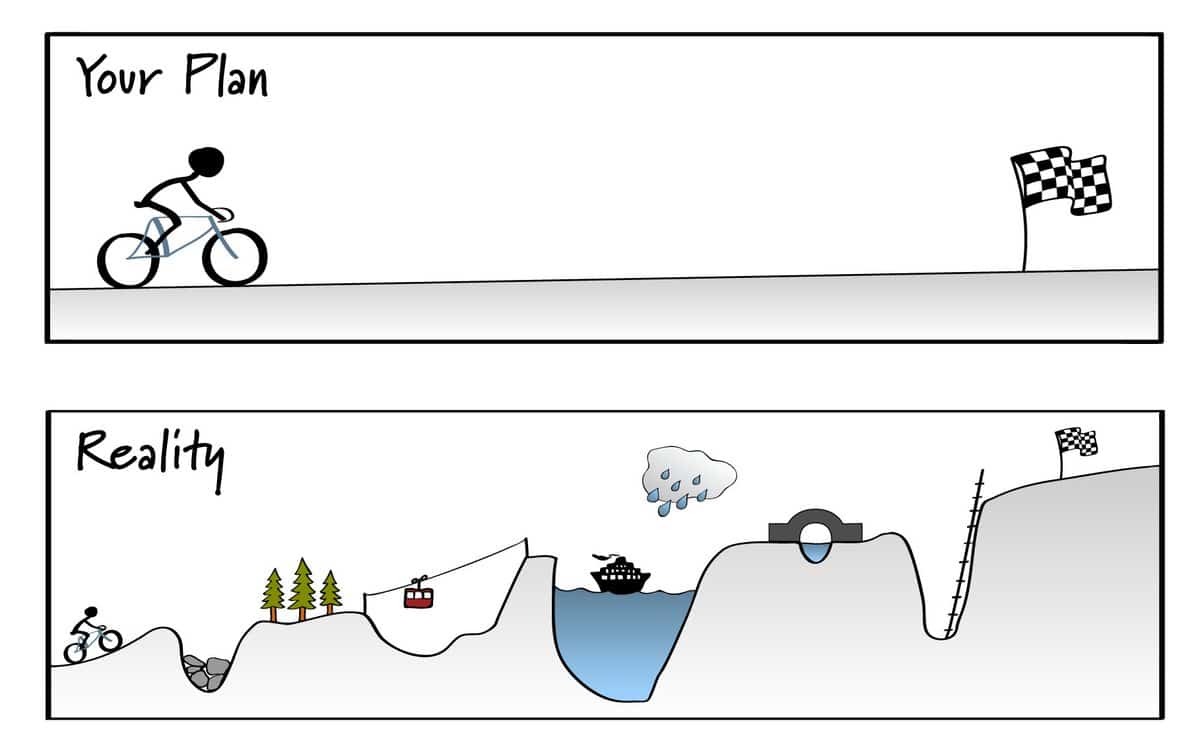

ideal vs. reality

When they did come out of Egypt, they experienced discontent. Now, coming out of Babylon, they experience apathy. In only slightly different ways at heart, their discontent and their apathy tell a surprising story: The Israelites really had no stomach for the reality of God’s promises. For it turned out that God’s promises demanded much of them. They demanded surviving lost in the wilderness, and they meant taking responsibility for themselves in their freedom. One circumstance led to resistance, the other to impassivity.

I have a feeling that the problem here is that the people believed that the ideal arrangement would be for God to take care of them. In an ironic way, that’s what they learned to expect in Egypt and in Babylon. For all the sorrow they endured, they learned to be taken care of, to have no real opportunity or responsibility for themselves. The world they imagined outside of bondage was one in which they would be taken care of but had none of the bad parts of living under subjugation. For those coming out of Egypt, it would be a land, quite simply, flowing with milk and honey; for those returning from the exile, it would be a restoration of the glory of Solomon’s time. No one had factored in the responsibility part. Gorbachev found a similar problem when freedom came to what was the Soviet Union.

When looking forward to an ideal, it’s awfully easy to imagine that it will be served up on a silver platter. And a corollary is true as well. If it’s supposed to be served up on a silver platter, and then it’s not, what do you make of that? When the promised land seems to turn out to be wandering lost in the desert, when the restoration of Zion turns out to be living adequately in the wreckage of former times, what do we make of it? The Israelites answered with grumbling in the first case and indifference in the second. Both are ways of dealing with the perceived absence of God. In the Exodus and the return from the Exile, the Israelites began to believe that God wasn’t present, because the grandeur, the success they had expected was nowhere to be found.

Enter Haggai

Into this environment comes the prophet Haggai. Twenty years after the edict of Cyrus the restoration of Jerusalem’s temple is incomplete at best. Haggai recognizes the depression into which the people have fallen. He also recognizes that it is time to break out of it, out of the cycle of malaise.

Haggai begins where we all need a beginning when we are in a place of listlessness and spiritlessness. Haggai begins by boldly claiming to the people that despite appearances to the contrary, God is present with them now. Even though they can plainly see that the temple is but a vestige of its former self, he cries, “I am with you, says the Lord of hosts, 5 according to the promise that I made you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit abides with you. Do not fear.” It is amazing sometimes how powerful can be the reminder that just because times are bad it is not a sign of God’s absence, how powerful can be the reminder that even in the depths God is present.

And then Haggai reminds them of what the presence of God can mean.

Once again, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land; 7 and I will shake all the nations, so that the treasure of all nations shall come, and I will fill this house with splendor, says the Lord of hosts. God will shake the heavens and the earth and the dry land.

The Israelites are reminded of the active spirit of God. They are reminded that God is passionate and powerful and full of possibility. Haggai reminds them of this, now, not so they may wait impassively for God to do things for them, but so that they may find their own hearts on fire once again.

Haggai looks out at the incomplete shell of the temple. He says, “Is it not in your sight as nothing?” and he challenges them to make it something. He reminds them of God’s powerful presence, as a help and an encouragement to them. But more especially he reminds them that they will not emerge from the doldrums until they take their part in the future, until they rebuild and reestablish the center of their worship life. For then they take their own part in the shaking of the heavens and the earth and the dry land.

Haggai reminds the Israelites that they have a part to play in rebuilding the temple

The meaning of “I will shake the heavens and the earth”

This message from Haggai may sound somewhat disengenuous, I suppose. At any time when people look around themselves and see that things are not lining up with God’s promises or the glory of other times, when the church is half empty, when injustice seems to have won the day, when hope begins to feel naive, when family life is full of stress, when worries pile one on the other, when we look around and see these things, we may find Haggai’s pep talk to be shallow and pollyannaish.

But before you reject it out of hand as too simple-minded, consider these facts. For twenty years the rebuilding of the temple limped along aimlessly. Then, on August 29, 520 b.c.e. Haggai comes on the scene to encourage Zerubbabel, the governor, Joshua, the high priest, and the people at large to take up the project again. He reminds them that God is present and can shake the heavens and the earth and the dry land, and that they can expect as much from themselves. Though the work on the temple would not be fully complete until four years later, in 516, by December 18, 520 b.c.e. enough progress has been made that the temple is then reconsecrated for use. In a mere three and a half months, the temple is taken from ruins and completed enough for use. In addition, the full completion of it assured a few years later.

If a group of discouraged repatriates from the Babylonian exile can accomplish so much in three and a half months, what is keeping any of us from doing the same? Look about, and what do you see in your life? If what you see is “in your sight as nothing,” if you look out and find discouragement or disappointment or malaise, if it makes throw your hands up and shrug your shoulders, let the words of the prophet Haggai wash over you:

[T]ake courage, … says the Lord; work, for I am with you, says the Lord of hosts,…. My spirit abides among you; do not fear. 6 For thus says the Lord of hosts: Once again, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land.

Let the passion of this God enter your heart and set it ablaze. For you may build more than you dreamed possible; you may soon consecrate as holy what even now lies in ruins. Let your being free; let the heavens and the earth shake; let the rebuilding begin. Amen.

A sermon preached at North-Prospect United Church of Christ, Cambridge, Massachusetts by Rev. Dudley C. Rose

Date: November 11, 1998

Text: Haggai 1:15b-2:9